Why does the Septuagint have so many differences from the Hebrew text of the Old Testament?

Over the past few years I have compared many Old Testament passages

in the Masoretic Hebrew text and the Septuagint as I have prepared to lead the

weekly lectionary study at my local Episcopal church. Sometimes there are no

striking differences, but often there are quite significant ones. Why do these

differences exist? I alluded to the reasons briefly in an earlier post. I will

now give more details.

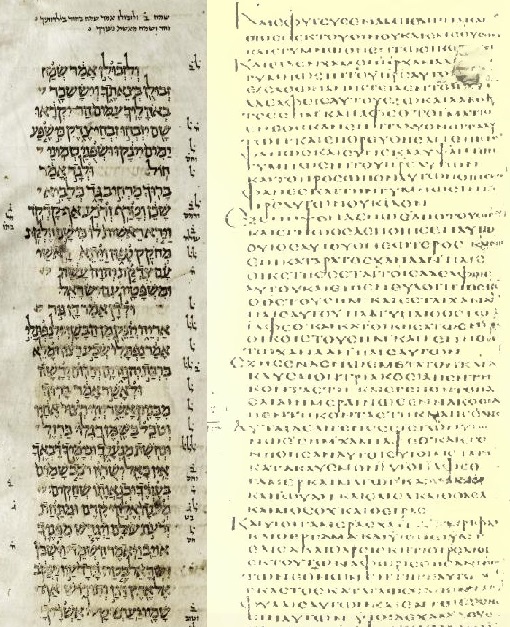

1. The original Hebrew text had consonants but no vowels. In

modern times we are accustomed to thinking of the vowels of the Masoretic Hebrew

text as definitive. In many cases, though, different vowels are possible and

make just as much sense. Sometimes the vowels that presumably underlie the

Septuagint’s translation actually make the text easier to understand.

2. Manuscripts were handwritten. Letters could be confused

with one another, depending on the scribe’s style of handwriting. ר (r) and ד (d), ו (w) and י (y), ב (b) and כ (k) are among the

pairs of easily confused consonants. At least one of the Dead Sea scrolls has

the peculiarity that the tail on י (y) is regularly drawn longer than the tail on ו (w)!

3. There were no spaces between words. There could be

differing decisions about where one word ended and the next began.

4. Readers might accidentally or deliberately transpose

letters. Accidental transposition is common enough in any language. Deliberate

transposition can happen when the reader cannot make sense of the string of

letters as it stands. By rearranging two or more letters, and perhaps even

changing one or two, the translator was able to understand an otherwise obscure

bit of text, and he translated it into Greek according to this understanding.

5. Some Hebrew words were rare or obscure. Since scholarly

lexica had not yet been invented, translators sometimes had to use their best

judgment based on the context. As suggested in the previous point, deliberate

rearrangement of letters was another way to deal with this problem.

6. The translators were in a historical time and cultural

environment very different from that of the original writers and revisers of

the Hebrew and Aramaic scriptures. Greek-speaking Jews in Alexandria, Egypt in

200 B.C.E. had a different geographic orientation from that of Hebrew-speaking

Jews in Palestine before the exile, or Aramaic-speaking Jews in Babylon or

Persia during the exile.

We will see examples of many of these phenomena while

examining specific passages in the future.

A brief word about the Masoretic text of the Hebrew

scriptures is in order. The name of the Masoretes comes from the Hebrew word masorah

‘tradition’. The Masoretes were a group of Jewish scribes active in Israel and

Babylon in the 7th-11th centuries C.E. They lived long after Hebrew had ceased

to be a living language. They inherited traditions (thus their name) of

pronunciation and interpretation from their forbears. They devised elaborate sets

of symbols to indicate vowel sounds, intonation or melody, pauses and other

breaks in the text. They also came up with a large set of marginal notes with

corrections to the consonantal text, statistics, and so forth. (A short

introduction to these can be found in A Simplified Guide to BHS, 4th

ed., by William R. Scott; Richland Hills, TX: BIBAL Press, 1987. A more

comprehensive introduction is The Masorah of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia:

Introduction and Annotated Glossary, by Page H. Kelley, Daniel S. Mynatt

and Timothy G. Crawford; Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1998.)

The first complete Masoretic manuscript of the Hebrew

Scriptures was completed in 930 C.E. by Aaron ben Moses ben Asher. This is

more than a thousand years after the Septuagint was translated, about 200

B.C.E. The Masoretic text is the basis of all published editions of the Hebrew

scriptures. Thus it underlies all modern translations of those scriptures. Consequently,

when we in modern times see the differences between the Old Testament as we

know it at the Septuagint, our first inclination may be to consider the

Septuagint to contain errors. The wiser course is to consider each version of

this text to have its own value.

If you want to dig deeper, you will need to study the field

of Old Testament textual criticism, where you will also learn about the Latin

Vulgate and the Syriac Peshitta, which also predate the Masoretic text by

centuries. A textbook of this is Old Testament Textual Criticism: A

Practical Introduction, 2nd ed., by Ellis R. Brotzman and Eric J. Tully; Grand

Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2016.

©

2017 Paul S. Stevenson, Ph.D.

Comments

Post a Comment